By Kate Hawthorne, Arts Editor

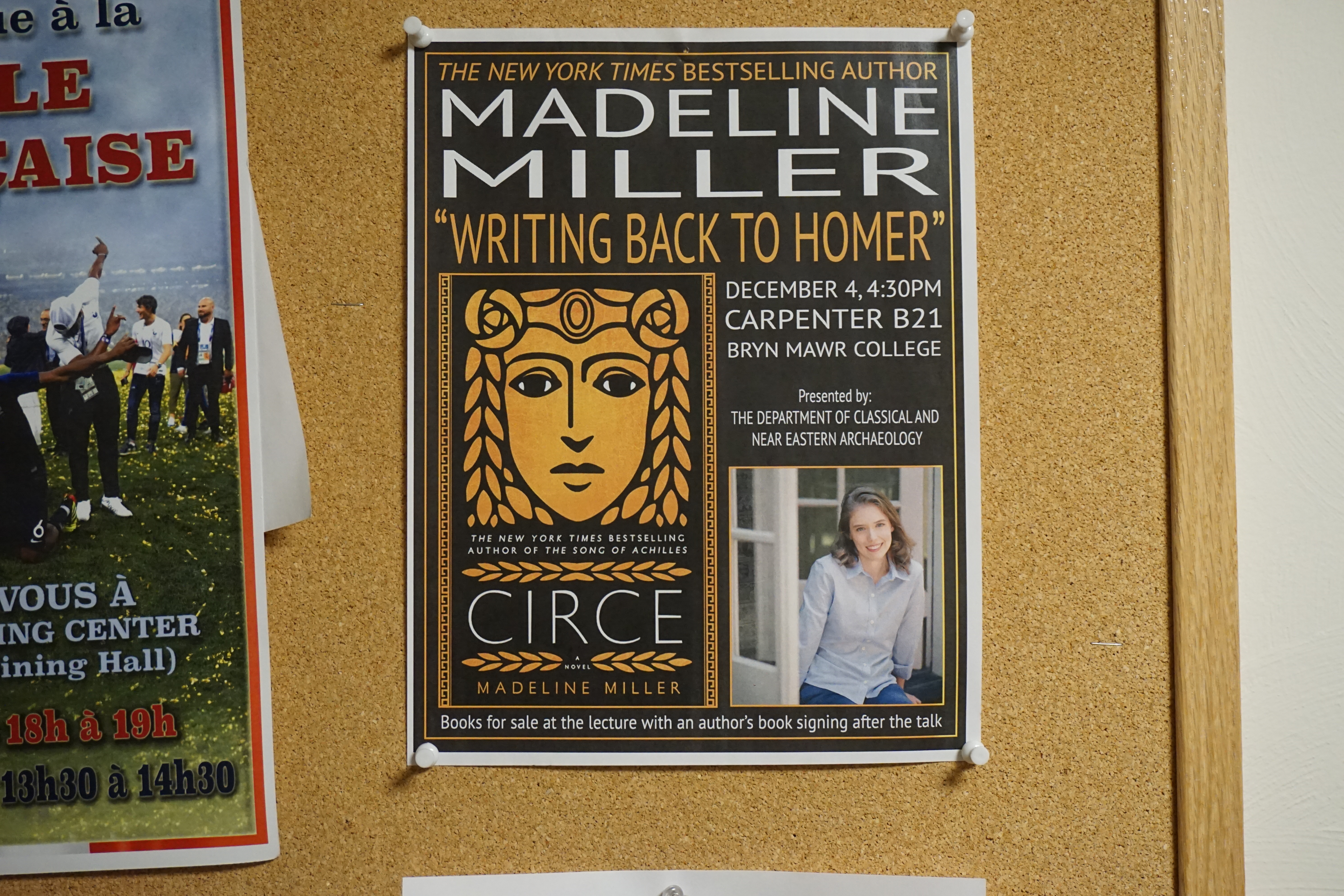

Madeline Miller, a novelist who first received acclaim for her 2012 debut novel and New York Times bestseller, “Song of Achilles,” visited Bryn Mawr last Tuesday to discuss her highly anticipated second book, “Circe.” Released in April 2018, “Circe” also quickly reached the top of the New York Times Best Seller list. In her talk, Miller focused on her latest novel, a reinterpretation of Circe’s story, a character who makes only a brief appearance in the “Odyssey.”

Miller began by discussing her own relationship to classical texts, describing how her mother read parts of Homer’s the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey” to her out loud as a child, but it was not until eighth grade that Miller first encountered the character of Circe when she read the “Odyssey.”

She spoke with passion about the interaction between Odysseus and Circe, which she found frustratingly anti-climactic. “He holds a sword to her, she screams, falls to her knees, begs for mercy, and invites him into her bed all in one breath,” Miller told the audience. “Can’t we just keep the camera on her a little longer? What’s her side of the story?”

One only needs to hear Miller talk about Circe to feel the depth of her passion. “Here’s this character,” she said of Circe, “she’s born a goddess, but there’s a part of her that belongs in the mortal world.”

Miller talked about how she came to her version of Circe, a conglomeration of myth, legend, literature with her own spin on it. She finds the idea of magic being passed down through her blood, as is implied by Homer, “really boring, as a novelist. I prefer when you create something of yourself.” Her interpretation of Circe, Miller reiterates, “was born a goddess, but became a witch.”

In writing the book, Miller worked hard to reframe what Odysseus described as beautiful, such as Circe’s braided hair. Rather than recreating Odysseus’ male gaze, Circe’s beautiful braids become something practical, an expression of Circe’s agency and her need for mobility.

Miller also turns other aspects of the mythology on their head, for example by making Odysseus the sex object. “Just as she is the sexy cameo in his story, he is the sexy cameo in hers,” she told the audience. Miller tries to reframe the mysterious characteristic of Circe in the Odyssey as one where Circe has agency and choice.

One of the most important aspects of this story for Miller, though, is how she focuses on Circe the mother and woman, rather than Circe the witch or the unknowable. She emphasizes that a birth scene can be a true epic, along with more “mundane” acts like changing diapers, gardening, cooking, and craftwork. These gendered tasks are generally dismissed, but Miller encourages us to see them as worthy of an epic.

When Miller reached the end of her lecture and opened the talk up for a question and answer session, students had plenty of questions for her. One student asked Miller whether she believes that Calypso and Circe were once one character, to which Miller responded “well, Calypso doesn’t have any lions,” before delving into how she sees Calypso and why the two characters are both very similar and very different. A number of audience members followed up with questions about popular culture, leading Miller to discuss Wonder Woman, Percy Jackson, and how Cersei and Circe are definitely similar.

When asked about her future novels, she told the audience that she is hoping to write one reframing Roman myth, like the “Aeneid,” or possibly retelling Shakespeare’s “The Tempest.”

She also was asked more serious questions about the erasure of queer/feminist/POC stories, and she shared that this erasure actually motivated her to work with the tale of Patroclus and Achilles that appears in her first book. In her studies, she realized that the queer relationship was not really present in the literature, despite being so established in ancient tradition, and she wanted to bring it back. “Song of Achilles” actually came out of an idea for her master’s thesis about interpretations of Patroclus and Achilles’ relationship throughout history.

“Circe” is a continuation of her quest to reclaim the narratives of marginalized characters in classical writing. The real danger though, she shared, is the danger of a single story. She explained that “if there’s just one story, we start to take that story as fact.”

Photo credit: Ethan Lyne