By Michael McCarthy, Staff Writer

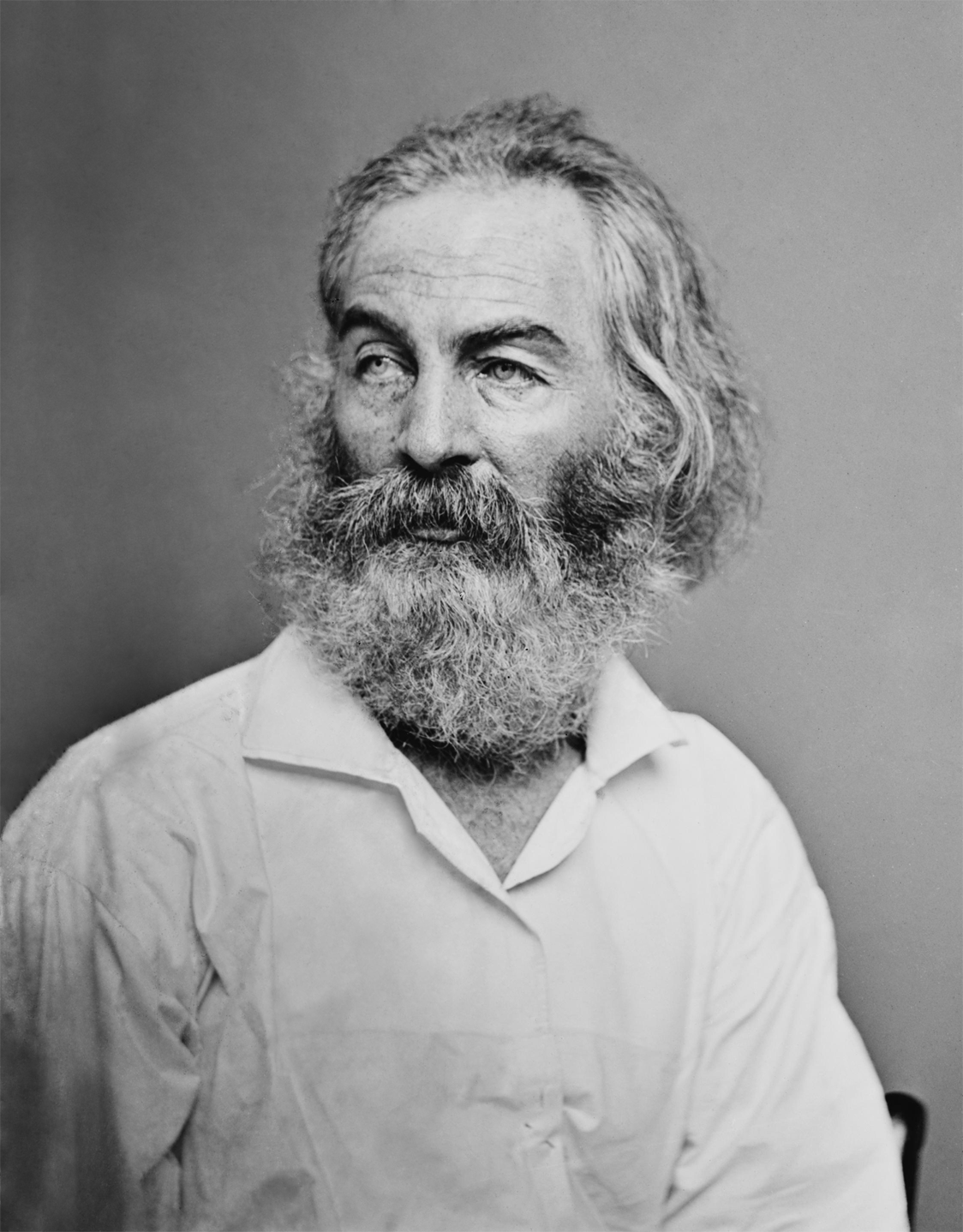

Two hundred years after his birth, a reevaluation has begun concerning the most American of American poets, Walt Whitman, and it is his American-ness which has caused such spirited debate. Deathbed Edition, performed in the Hepburn Teaching Theater in Goodhart Hall at Bryn Mawr College, engages this ongoing conversation by interrogating the assumptions, presumptions, and hopes of Whitman’s poetry.

The production, an original work conceived and written by the students, translated Whitman’s poetry to the stage not just by reading and performing his poetry but by incorporating its themes into the actors’ clothes. Through their costumes, their characters represent every rank of American society, rich and poor, blue collar and white. When they recite Whitman’s poetry, often overlapping the lines to produce a mesmeric effect, there’s a polyphonic quality so quintessentially Whitmanian, as if all of American society is being given a voice.

But who is Whitman, the play asks, to speak on behalf of an entire society? In one set-piece, lines of “Song of Myself” are read aloud, and the characters, standing in a line, raise their hand for each verse that describes them. Not once do they all raise their hands together. Later on, when Whitman emerges from underneath the stage to greet the characters, he is shunned. His appeals to universal experiences fall flat. It seems his poetic project, a plea for radical empathy that cuts across boundaries of race, class, gender, sexuality, anything, has failed. As one character notes, “Human bodies are words, myriads of words.” Perhaps Whitman doesn’t have them all.

Nevertheless, what Director Mark Lord describes as, “an incredible hopefulness in the poems and in Whitman’s outlook” is a welcome palliative to a world shadowed over by despair of the future. Deathbed Edition relates Whitman’s poetry to the current climate crisis, which, it seems, the younger generation became aware of after it was already too late to solve. Politically, Whitman wrote about the Civil War, “the other great crisis” in American history, but his poetry still resonates in the modern era. “He also writes really beautifully about the power of the Earth and our capacity to be connected to it,” Lord said. Whitman’s ideas may be outdated, but they are still indispensable in trying to understand where the nation stands in regards to its next great conflict.

Deathbed Edition makes no attempt to provide answers to the questions it raises, but the confusion at the set-pieces is part and parcel of the theater experience. The set-pieces range from the weird to the very weird. At one point, Whitman plays with a giant balloon as a character reads a description of a sentient blob, as if Whitman is trying to understand the blob’s properties. There’s an open mic where one character tells the moth joke, one almost sings a song before getting cut off, and another simply peels a potato. At one point, the characters zombify and become obsessed with their phones. By the looks of it, one is really trying to win her Mario-Kart race, another is tapping a dent into her phone, and yet another is going all-out on Tinder.

Whether funny or profound, Deathbed Edition never fails to be intriguing. To ascribe one meaning to the production is to do it an injustice. “I don’t think art aims to be understood,” Mark Lord said. “There’s not a message we want to deliver. It’s more an experience.” That it is. The cast offered a theater-piece of strange but undeniable beauty which is sure to perplex its audience but also prompt many meaningful conversations about Whitman, climate change, and the future of the country. Hopefully, the audience will find the words that Whitman couldn’t.

Image credit: Wikipedia