By Annarose King, Staff Writer

Quiara Alegría Hudes looked at home on the stage of Goodhart Hall’s auditorium. She had held a playwriting and dramatic writing workshop for students earlier in the day, October 18. By the evening, it was time for a conversation and a Q&A session. She would also read two sections from her memoir, My Broken Language, which was published this year. These two events were sequels to a writing workshop Hudes had led a month before, on September 20. Bryn Mawr Professor Jennifer Harford Vargas introduced Hudes and her well-known works, including the book for the Broadway musical In the Heights, and the screenplay for the 2021 film. She is also the author of Water by the Spoonful, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2012.

It was the first time that Hudes read aloud from My Broken Language for an audience. The trial run was engaging, humorous, and thought-provoking. Her voice carried all the sincerity and warmth that comes with knowing one’s writing by heart. In part of her conversation with Professor Harford Vargas, Hudes elaborated on the title’s significance. A playwriting professor at Brown, her graduate school, had asked if she wrote in Spanish or English. When Hudes responded that her writing was composed of a “broken Spanish,” her professor encouraged her to continue with this writing style. That conversation was, in part, where My Broken Language originated from. Hudes included “my” to balance out the emotional pull of “broken.”

Before turning to Chapter 28 of her memoir, Hudes gave the audience some background knowledge. While on a day trip with her college friends from Yale, they started discussing if they believed in a higher power. The other students in the car “were white or, like [Hudes], white-passing,” and some came from a variety of religious practices. Everyone else did not believe in God, no matter their familial ties to religion. “Do you believe in God?” is a more complicated question for Hudes, deeper than a casual conversation topic. She described a sudden inability to understand what it meant, in the context of her own beliefs. English could not encompass “you” when her aunt, mother, and grandmother influenced her with their own spiritual traditions. Belief was too small a concept to explain God’s role in her life. As for God, she would have to describe “Atabey,” and her “Abuela’s Jesucristo, mami’s Olofi Olodumare, Tía Moncha’s Virgen Maria”, guided by four languages. She broke down how each word felt incomplete for her, and the suffocating experience of her face heating up. While her memoir passage also explained the situation well, her preface had a more emotional layer. She seemed transported back into the conversation.

Hudes read the whole chapter. She described how the trees and mountains passing her in the car were a calming presence. Her friends were intrigued, but also confused, by her belief in God. The conversation eventually changed to another subject. In her memoir, Hudes noted how her friends were from English-speaking families, and how English defined their lives. One integral part of her family was that their “bodies were the mother tongue,” followed by Spanish, then English. She has studied more history since her time at college, including the history of her own family. She explained how Borinquen, or Puerto Rico, had linguistic changes or deprivations over time. “Taínos spoke various Arawakan languages and dialects” up until 1493 and the arrival of Spanish colonizers. The Taínos continued to speak their language, despite pressure to speak Spanish, and “were pillaged.” Their words became incorporated into Spanish, such as “‘Hurakan’, ‘boriken’, ‘barbacoa’” into “‘hurricane,’ ‘Borinquen,’ and ‘barbecue.’” As African slaves were forcibly taken to Puerto Rico, “Yoruba, Igbo, and other West African languages” came with them, and provided “resilience.” Once Puerto Rico became a U.S. territory in 1898, English started to replace Spanish in government, education, and other public places. Spanish would be reinstated as the main language for education in 1948. That wasn’t much solace for the two generations who were made to learn English or refused to attend school.

The second passage Hudes read was from Chapter 35, which focused on the women in Hudes’ family. She addressed her family members in the front row, joking that she hoped it would go over well with them. With awe and admiration, she praised how her “matriarch’s bodies were natural wonders,” delighting in their arms, legs, curves, hair, and scars. Her written odes transcribe “the messy book of womanhood’s flesh” perfectly. Her voice created layers of emotion, playing out a melody of humor and love.

The reading ended, and the Q&A started. Hudes and Professor Harford Vargas discussed her meta-textual details, childhood memories of Philadelphia, and the differences between screenwriting and playwriting. Several attendees asked about how language travels internationally, her advice to students about college, and how music influences her work. Hudes described how In the Heights would portray a dinner scene, with different versions for the musical and the film. She turned her chair to the side to show how people would eat onstage in a play. With the film version of In the Heights, she could incorporate close-ups and facial expressions into the story. She asked her mom to send photos of homemade food as inspiration for the dinner in the film.

Hudes was raised as a musician, and knew she wanted to play music. She described how there was a satisfaction to playing the piano; she could have some time to herself. She was used to staring at a wall all day to write, as she gained a similar patience from playing music. She elaborated on how her major at Yale was music composition, yet her art had expanded beyond music. We don’t have one path in college, Hudes explained, adding that we have many paths throughout life. With the conclusion of the Q&A, we all applauded.

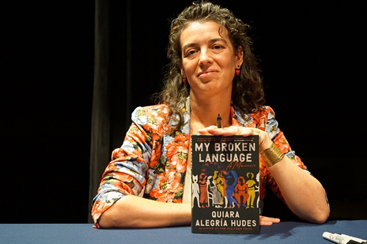

As Hudes moved to a small table stage left, audience members stood up from their seats. Students went up the steps on the other side of the stage, carrying their free copies of My Broken Language. Hudes took a few moments to chat with each student while she signed their book, as she recognized attendees of her two workshops. The chance to hear Hudes talk about her own various paths in life was extremely fulfilling. Her memoir is as vivid as her personality, and meeting her in person left an inspiring impression.

Image credit: Annarose King