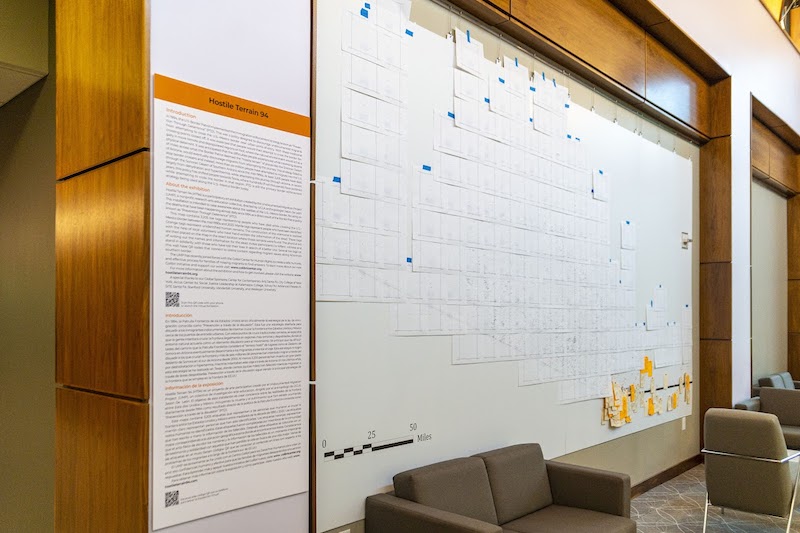

Hostile Terrain 94 hangs in Lutnick Library, parallel to the North entrance. The piece is floor to ceiling, a striking array of orange and yellow labels slowly accumulating over time. From far away, the pattern is nothing foreboding, but once up close, the labels reveal themselves to be toe tags, marking up a wall map of the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. Each toe tag is marked with the information of an identified or unidentified migrant who has died attempting to cross the desert. Visitors participate in the creation of the piece by copying data onto tags by hand. As the project website states, the piece is “sponsored and organized by the Undocumented Migration Project, a non-profit research-art-education-media collective, directed by anthropologist Jason De León.”

On November 3rd, the library held an open session for all members of the Haverford Community to aid in the progression of the project. Other academic classes were offered the chance to participate during hours of instruction prior to the session, thus the piece’s bottom right corner is already covered in tags. At noon, I arrived in Lutnick to meet Semyon Khokhlov, an exhibit organizer and research and instruction librarian at Haverford College. He gave me an envelope filled with pages of data, a stack of toe tags, and a pen. The task began clerically: transpose data onto a tag, cross the name off the list, move on. However, the more time passed, the more weight each tag carried.

Though the exhibit is, in Khokhlov’s words, “a very powerful and personal way of confronting the details of the issue,” there is also some sense of bureaucratic action juxtaposing whatever personal connection a participant might have to the data. I filtered through descriptions of “skeletal remains,” “decomposition with focal skeletonization,” “skeletonization with articulation and ligamentous attachment,” and crossed-off names. Each line drawn through a column of data evoked erasure. As a participant, you are honoring the individuals who have died, yet simultaneously acknowledging their presence in your life as a mere set of information penned onto a card stock label. The intention seems to be to bring visitors to understand the inhumanity of how many migrants are left unidentified and undocumented, while also attempting to recontextualize the process and bring humanity to the forefront.

Khokhlov tells me, “the experience is born from traditions of participatory exhibits, and defined by active engagement. Participation involves recording this date onto a toe tag, so you’re doing this for someone else. It’s also handwriting, and it’s a lot of information, so it’s really a reflective exercise. The act of writing simulates and provokes real feeling and engagement.” Having an active hand in the documentation exercise connects you to the reality of how the data was documented originally. The confrontation with each name, and the abundance of names to confront, manifest as a kind of visceral awareness.

Why bring visceral awareness of the topic to the Haverford campus? Brie Gettleson, former Social Studies librarian at the college, has a background in Latin American studies and was the one to bring the exhibit to our community. When asked about her possible motivations, Khokhlov answered, “it’s a live issue, and it can be thought of in an abstract way, in terms of media coverage and seeing things on the news. But this is a very powerful and personal way of confronting the details.” Rather than let the Haverford community of scholars learn the experiences of migrants through media representations, we have been given the opportunity to look into the face of the issue, or rather, the faces of those affected.

The exhibit will remain in Lutnick Library all semester. On November 29th, Perla Torres, Family Network Director at the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, will be giving a related talk in Lutnick 200.