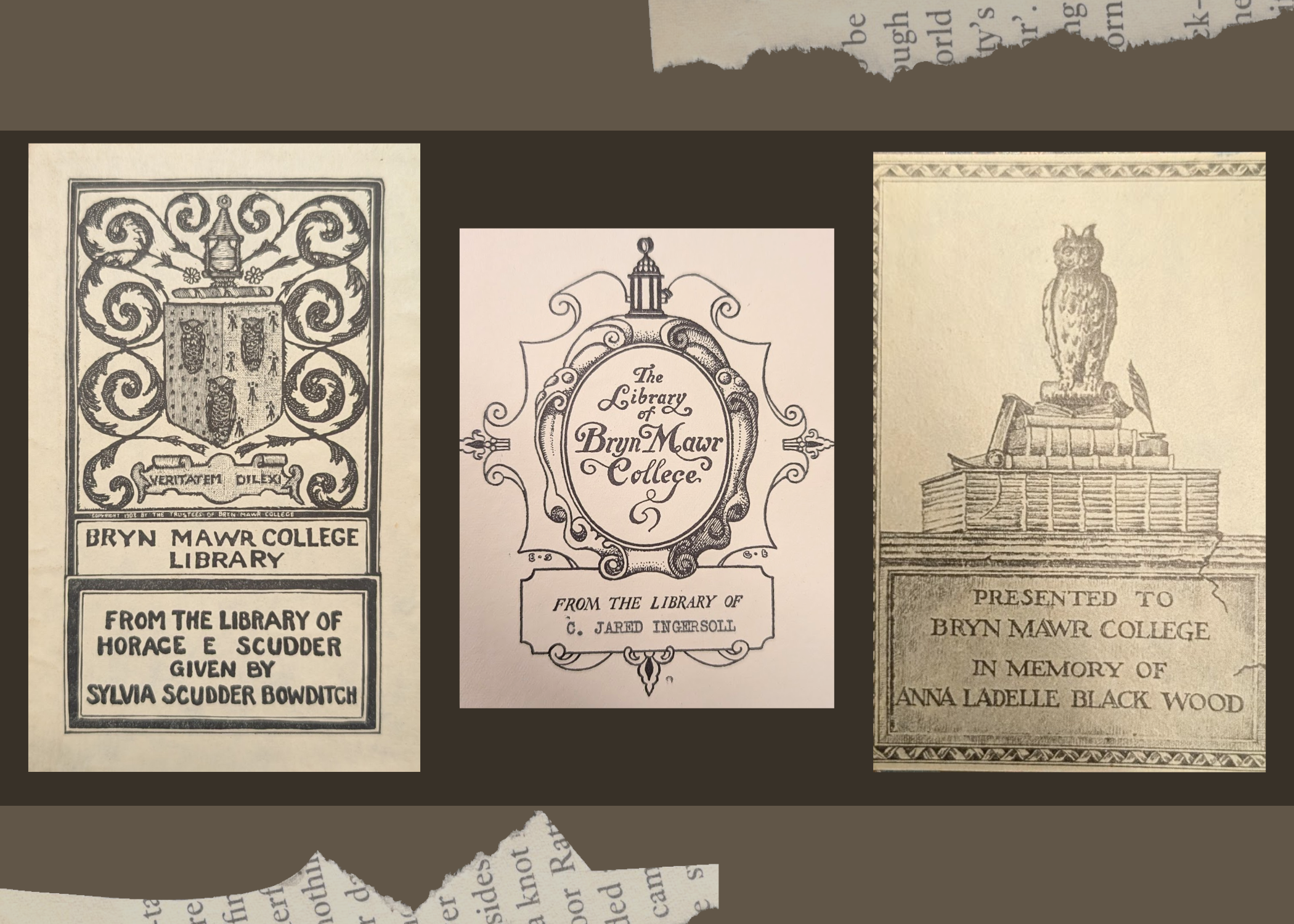

A story is not only found within the pages of a book itself, but sometimes within the inscriptions and doodles in the margins, left-behind bookmarks, and bookplates that tell a different tale: that of the life of its previous owner.

This is one of the reasons why I love perusing the old, tattered-spine books in Carpenter or on the second floor of Canaday. There, you are most likely to find an inscription dated back to 1884 memorializing a lost son, or a bookplate labeling a book from the library of Charles J. Rhoads, a Haverford College graduate who became the first governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia in 1914.

As it turns out, I am not the only one interested in the history that these inscriptions and bookplates document. I spoke with Berry Chamness, the Director of Collection Management and Discovery at Bryn Mawr College, who informed me that “there was a project that we, the college, the libraries, and Library & Information Technology Services, participated in — Book Traces — [where] they looked at inscriptions, marginalia, [and] things that were written in the books.”

Book Traces is a running project founded by the University of Virginia in 2019 where people can upload photos of such features found in library books published prior to 1923. Due to Bryn Mawr College’s abundance of library books from the 19th and early 20th century, it was chosen to participate as one of the partner libraries.

In a time where academic libraries are increasingly digitizing access to these books, Book Traces was founded as a way to discover and document these features that are full of historical insight: acting as proof of what we will miss if we continue along this path.

So, in the spirit of Book Traces, let us see just how much history we can glean from a physical book.

In Canaday, I found a book titled Poetry for Children, a bookplate designating it to be from the library of Horace E. Scudder, an author best known for his children’s books. However, my intrigue lies in the person who gifted it: Sylvia Scudder Bowditch.

I searched her name, originally not expecting to find anything. It turned out that Sylvia not only left books to Bryn Mawr, but also her scrapbook. I went to view the book in Bryn Mawr’s Special Collections.

Sylvia’s scrapbook extensively documents her life from 1895 to 1906, including her time as a Bryn Mawr student from 1899 to 1901. Sylvia graduated with degrees in both Greek and French.

As you open the scrapbook, you are greeted with a record of the exams Sylvia had to pass in order to be admitted to Bryn Mawr. They range from Chemistry, to Greek and Roman, to even Botany, which Sylvia notably received high credit for. There is also a copy of the Class Song of 1889, written entirely in Latin, and photos of vine-covered buildings around campus with the quote “Here’s to Bryn Mawr College, she’s the source of all our knowledge.” In this way, Sylvia seems to commemorate her beginning at Bryn Mawr.

Continuing through the scrapbook, it is evident that Sylvia loved music and theater from the numerous ticket stubs, playbills, and orchestra programs that she collected. There are also pages dedicated to letters from friends, which even include the envelopes they came in. Many of them were written in a cursive that at times, I thought veered off into a different language. Interestingly, the only letters written in print were from a mysterious admirer.

We also get a glimpse into what the student government was concerned with. Sylvia kept a notice sent by the then-called Bryn Mawr Students’ Association for Self-Government, announcing a meeting on March 8, 1896 “concerning change in time of Annual Elections.” There is also a list of resolutions, some a particular product of their time. One describes how a student could not receive men in their studies (their room) without a chaperone.

My favorite items in Sylvia’s scrapbook, however, are the newspaper clippings she kept regarding the college. One article commended The Girls’ Fire Brigade of Bryn Mawr College. The students put out a fire in a professor’s home, who supposedly had no clue his house was on fire until he was shown the flames. The article also includes a sketch of the brigade.

The scrapbook ends with a bittersweet article dated Jun. 5, 1906, sharing life-updates of the college alums, including Sylvia. It announces her marriage to Ingersoll Bowditch on Oct. 18, 1904. The question is, was Ingersoll Bowditch the author of those mysterious love letters?

We may never know the answer; however, with just a name found in a book chosen by pure chance, and thanks to Sylvia’s meticulous scrapbooking, I stumbled upon a treasure trove of information.

While academic libraries may be progressing towards a digital route, we can rest assured that Bryn Mawr students seem to be holding tight to physical books. At the end of our discussion, Chamness mentioned that he and the library staff wondered if they should begin purchasing more e-books and fewer print books. He stated that they began “asking different students in the library whether they still liked print books, and the answer was always, ‘Yes, we still like them.’ And that was borne out in the data from a MISO [Measuring Information Service Outcomes] Survey that if they needed to read a whole book, whether for class or for pleasure, they still would prefer the print book.”

Thus the chances are good for more physical books being donated by alums, and for future generations being able to sleuth out traces of Bryn Mawr history, keeping students and alums connected across time.