By Anna Hsu, Co-Editor-in-Chief

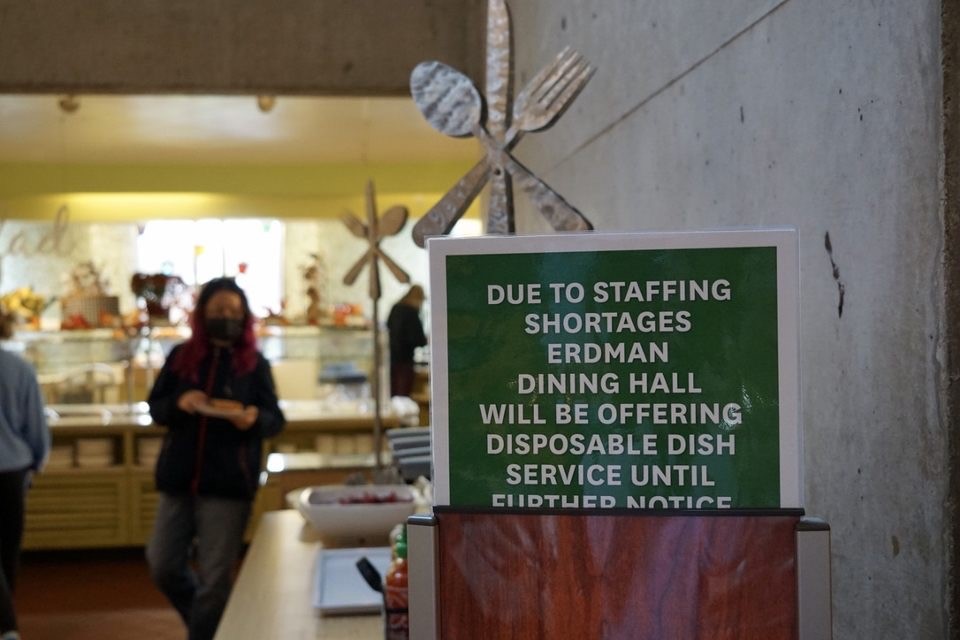

As Erdman’s dish room reopens and we can once again use ceramic plates and silverware, students have started to settle into a consistent dining experience. However, the burden on our dining hall staff has only increased. The fall semester has been marked by 30-minute long waits, staff shortages and a switch to disposable cutlery. During the first few days of September, lines at Erdman stretched to the outdoor entrance. At New Dorm, when the Mikasa specialty bar first opened, throngs of people looped all the way from the hot food to the dessert bar. Wyndham Grab & Go has been postponed to help support the staff at Erdman. At Haverford, paper plates and disposable cups remain in use. Many student workers have complained that they are running on fumes.

A National Issue

A severe labor shortage in the food service industry has impacted campuses across the nation. Dining halls from Stanford to West Virginia University have reported staffing issues, increased student traffic and limited menu options. Haverford and Bryn Mawr are no exception.

Interviews with anonymous Erdman supervisors and workers have revealed even more worrying concerns. Some full-time staff, including managers, have had to take leaves of absence for mental health reasons or due to workplace injuries. Other workers are unable to take time off because of the burden they fear it will place on their fellow staff who are already suffering. “Everyone’s been calling out sick but we just stopped caring [about getting more workers],” stated a supervisor. “Now we’re just understaffed.” In addition to its dwindling numbers, overworked staff are not given hazard pay (as stated in Bryn Mawr’s 2020 Town Hall) and sick pay for students has been reduced to 15 hours maximum.

An interview conducted over email in early October with Bernie Chung-Templeton, Executive Director of the Bi-College Dining Services, provided an administrative perspective on the issue. “It was extra hard this year because we didn’t get the full complement of students we normally get,” she replied when asked about conditions for full-time staff. “We have modified, reduced and simplified our services to account for the lack of staff. All positions are posted and advertised. Applications are reviewed as they come in. […] There is a nationwide shortage in the foodservice [sic] industry. Our experience isn’t unique.”

When asked about Wyndham’s closure, Chung-Templeton replied that the staff was “reassigned…to support Erdman” because of “staff shortages due to vacancies and staff out on medical leave.” As of the time of publishing, Wyndham Grab & Go has still not resumed operations since its postponement in October.

“Everything she said is true,” said an Erdman supervisor after reading Chung-Templeton’s responses, “but it’s not the whole picture.”

Inadequate Pay

It is hard to stomach special events when they are dependent on the labor of our already-overworked staff. The Defy Expectations campaign celebration held on October 1, which commemorated Bryn Mawr’s record-breaking $301.8 million fundraiser, was set up and run by dining hall workers. The tone-deaf announcement of surpassing the original $250 million goal was a slap in the face to full-time staff and student workers, whose wages have been left untouched. The starting minimum wage for full-time staff was only recently increased to $15 an hour, which had been a concern since at least 2016. It’s ridiculous that it even took so long for the $15 wage minimum to be instated for our full-time staff when it barely meets the requirement for an individual’s living wage in Montgomery County. For many of our full-time staff with families, a minimum wage of $15/hr simply isn’t enough.

Supervisors at Erdman have reported that first-year student workers have even missed out on traditions because they needed to work during Parade Night and Lantern Night. Student workers are classified as “level 1” workers and paid only $10.40/hr, with a measly $0.20 raise per 125 hours worked. Even though workers’ responsibilities range from cleaning to cooking to organizing to setting up venues, they are still paid less than less strenuous jobs like student teaching assistants and lifeguards, who are classified as level 2.

I remember working during Bryn Mawr’s Holiday Dinner celebration in December 2019, where staff were expected to assemble and deconstruct the venue in freezing cold temperatures. I worked a three-hour shift which involved herding students into a line to wait for a horse-drawn carriage. I stood shivering in the dark, the long hours further exacerbated by the monotonous work of organizing students into groups. The minute-long breaks I took were spent trying to warm my numbed toes near the barrel fires, while other students munched happily on meat pies and sipped warm cider. Call me dramatic, but I don’t think sneaking a bite to eat during a five-minute shift constitutes a celebration. The people who deserved a break the most—our supervisors and full-time staff—were working, many out of necessity, during the entirety of the night. To top it off, we were paid the exact same amount, even though the working conditions during the celebration were far more taxing than usual.

Allocation of Funding

During a budgeting workshop on Tuesday, October 19, Bryn Mawr’s Chief Financial Officer Kari Fazio explained the College’s financial situation. Fazio stated that the dining hall labor shortage was not due to disproportionate budget spending. Instead, they attributed it to “The Great Resignation” of many food service workers across the nation.

The Dining Services administration seems to agree that the blame lies outside of Bryn Mawr. “The benefits the College offers all its staff including [Dining Services] is very generous and unsurpassed in our industry,” Chung-Templeton wrote. “This isn’t my opinion but by comparison to similar jobs/work.” But seeing as Pennsylvania currently lacks laws surrounding sick leave of any kind, paid hours for sick leave may be marketed as a benefit when it should be a necessity.

Many have turned to Bryn Mawr’s endowment as the solution to the problem of inadequate pay. But the majority of Bryn Mawr’s hefty endowment of over $1 billion, accountable for 34% of the College’s revenue, is not actually spendable money. In the budgeting workshop, Fazio explained that the majority of the endowment is reinvested to account for operations, inflation, and fees. Then there is the draw itself, the amount of money that can be distributed from the endowment. The College cannot spend the actual value of the draw, only the interest accrued. They are forced to cut programs if the draw declines. Bryn Mawr technically has the ability to “pre-spend a gift,” or to spend a gift that has not yet accumulated earnings, but it is a practice they avoid.

Fazio said the College does not spend money that is not “reliably recurring” on “reliably recurring” expenses. The school cannot become reliant on the endowment to fund the wages (a “reliably recurring” expense) if they are not confident they will have the same endowment funds during the following year. However, many are critical of colleges’ endowment allocation processes, believing them to not fully serve students’ needs and only furthering the wealth gap between elite institutions and other schools.

Considering how we are in the middle of a pandemic, I’m of the opinion that Bryn Mawr should spend more money to help us have a closer-to-normal experience of college life. If the purpose of an endowment is to preserve intergenerational equity, why is Bryn Mawr not spending more to alleviate inequity in the current moment? Doesn’t the very definition of equity involve providing on an as-needed basis?

Lack of Transparency

There is also much to criticize about the lack of transparency between essential workers and administration. An anonymous Erdman supervisor reported an offhand meeting with President Kim Cassidy, who seemed unaware of the immense pressure on dining hall workers. The 2020 strike only exacerbated existing divisions between students and administration, who have been notoriously opaque in communications with staff requests and emails. Student workers are already bombarded with endless emails asking for shift subs. The only method of communication, supervisors have complained, are vague directions from administration spread by word-of-mouth. Rumors about dining services have thus begun to spread unchecked through campus.

Some workers have blamed the shortage of first-year workers on Bryn Mawr’s decision to over-enroll first years who could pay full tuition. However, others have noted that students deferred and took gap years in 2020, which would account for the larger-than-normal first-year class (assuming Admissions did not change acceptance rates). The Class of 2025 profile has still not been published, though word-of-mouth from students and faculty have confirmed a lack of first-years on work-study and a marked decrease in the number of international students. Although it is unclear if this is simply a coincidence, the sheer amount of students on campus are contributing to the stress and burnout of many dining hall workers. There are simply too many students and a dearth of workers who can keep up.

Other more outlandish rumors, such as funding being taken from the SGA budget, were emphatically rebuffed by Chung-Templeton. (Another controversy earlier in the semester involved requiring student clubs to purchase food from Wyndham, though this rule has since been revoked.) Chung-Templeton herself has not been able to confirm the proportion of work-study students who are first-years.

Disrespect and Invisibility

Along with long shifts and low wages, student workers and full-time staff are consistently slighted and alienated. A newly-created Instagram page @bmcdiningconfessions has shared grievances from dining hall student workers. Their experiences range from feeling ostracized during shifts to enraged at blatant disrespect: “One of your moms threw trash at me on parents weekend”; “The way that so many of us are close to quitting — this school needs to do SOMETHING soon”; “I’m sick and tired of rich people suggesting I cut back on hours if I ever mention being tired or stressed. That’s not how it works! Some of us are working to survive…”. Their Linktree, linktr.ee/bmcdining, includes a Google Drive folder with documents including email templates, unaddressed issues, and pay transparency of administration.

The conditions within the dining halls are also horrific, to put it mildly. At Erdman, despite complaints from students and staff, there is no air conditioning or temperature regulation. And although students are required to attend a short “Humanizing the Hat” program as part of their first-year orientation during Customs Week, many are still rude and condescending to workers. Basic etiquette is laughably absent, as students inconvenience dish room workers with tea bags tied to cups, chewed gum, used bandaids, bloody napkins, and moldy takeout boxes heaped onto the accumulator. An unused tampon was allegedly stuffed alongside the metal utensils.

As a worker at New Dorm Dining Hall for two years, I can attest from personal experience that it is a thankless and grueling job. When I put on the bandanna, I vanished into the background. I received no acknowledgement from students while I swept up crumbs, wiped sticky counters, refilled napkins, and organized food labels. Like many other workers, I became invisible—my friends who I met in class and extracurriculars barely acknowledged my presence. As workers, the thanks we got came in the form of a pitiful hourly wage and a few napkin notes (and not all positive; there were quite a few complaints about menu variety and the absence of certain sauces).

The sheer monotony of dining hall work does not bring about a sense of spiritual fulfillment, believe it or not. I can’t even imagine how much more difficult the situation has become during COVID. Workers don’t want paltry and performative gratitude, they want better pay that reflects the thanks they’re due.

At the Tipping Point

We depend on our workers to provide our food, which (to point out the blatantly obvious) we consume on a daily basis. If our workers are not paid well, quality suffers. It doesn’t take a genius in economics to realize that if we want more people to work, we should increase the benefits given for such a task—especially one that is demonstrably essential for daily living.

I have only been able to report on Bryn Mawr’s side. Haverford’s Dining Services are undoubtedly dealing with similar issues. The way the Bi-Co is treating its dining staff is not only untenable, it’s degrading. As a Bryn Mawr supervisor stated, “The general consensus is that people are so tired and ready to quit. The only reason why we aren’t is because we don’t want to leave the full time workers to run everything. We’re trapped. That’s the very clear sentiment and belief between all of us.”

Photo credit: Annarose King, Staff Photographer